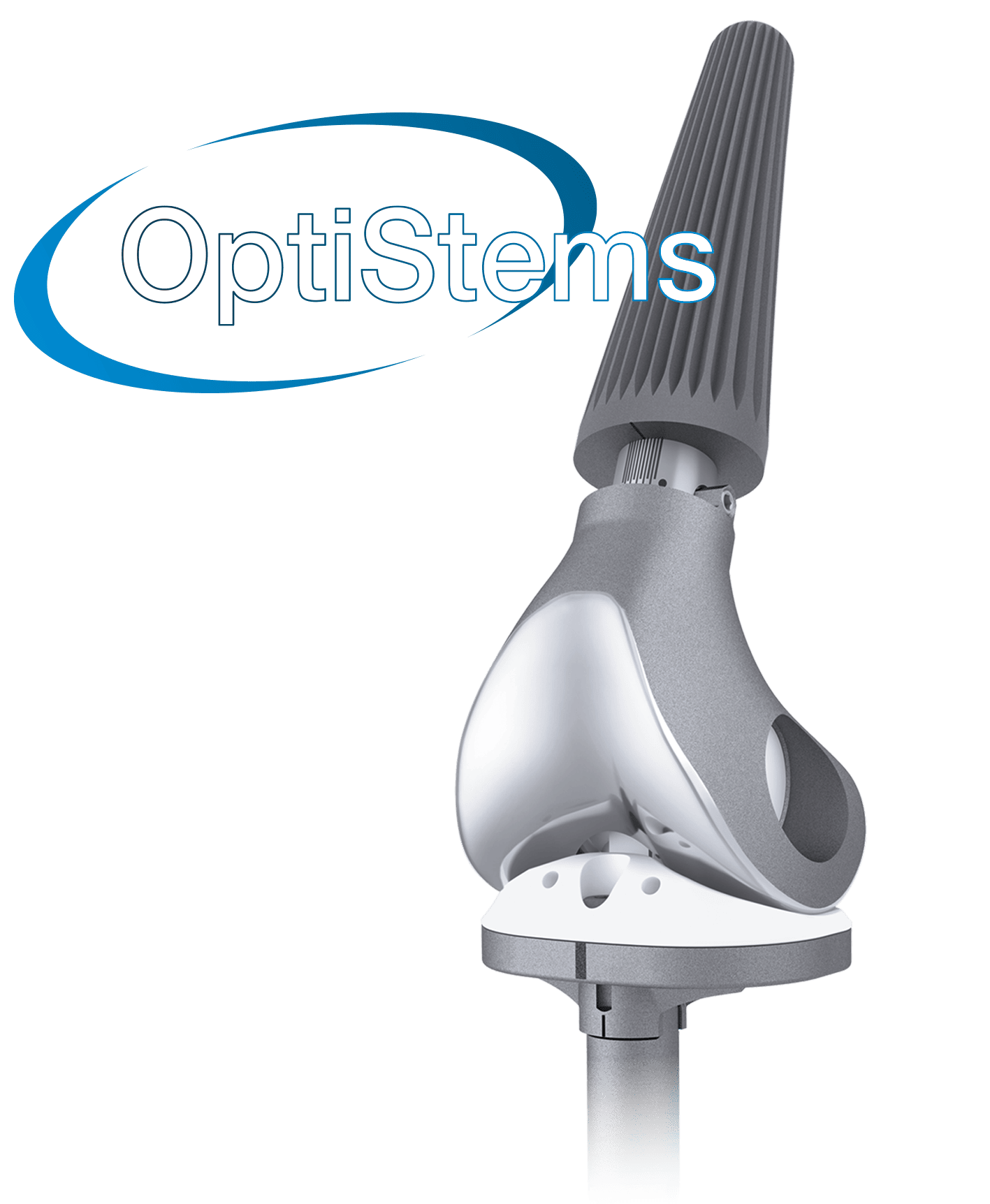

U.S. Surgeon Casey Whale’s Perspectives on the Anatomical Link OptiStem in complex TKA Revisions

Casey Whale’s OptiStem playbook for tough TKA revisions:

In this interview, Casey Whale shares a clear, anatomy-first approach to Link OptiStem in TKA revisions and select complex primaries. He prefers broach-only canal prep when the femur matches implant geometry and uses brief fluoroscopic reaming only to relieve a tight proximal choke point, with bone preservation in mind. Because the fluted, cone-shaped, fit-and-fill stem can create hoop stress, he typically places two prophylactic cables—one at the anticipated distal tip and another around the middle to proximal third, especially in fast-tapering canals.

He broaches to a firm mechanical stop and does not chase “proud” or “sunk.” If the stop is too deep, upsizing one stem size brings about 5 mm of length without changing other components. He re-establishes the tibial joint line first (fibular head, patellar tendon length), then fine-tunes length and tension with 0, +5, and −5 mm adapters, and sets rotation at the adapter

in 5-degree steps, while the stem seats where the canal dictates. Adopting a revision-hip mindset, he chooses stem length to bypass the defect by about two cortical diameters; 100 mm covers most cases, with 130–160 mm reserved for prior hardware or diaphyseal defects.

Read or watch the full interview with Casey Whale, M.D. on VuMedi ...

What’s your current Link OptiStem case count, mean follow-up, and early outcomes?

Casey Whale:

I’m at about 20 Link OptiStems right now. Outcomes so far have been really good. I’ve had one complication. Otherwise, they’ve done very well.

Which intra-op cues make you switch from broach-only to targeted proximal

reaming, and to what diameter relative to the planned broach?

Casey Whale:

I switch to targeted proximal reaming mainly in smaller female patients with very narrow femurs. The intraoperative cue is that the broach clearly hangs up proximally, while there’s still room distally. If I can’t seat even the size 1 OptiStem broach, I’ll perform limited proximal reaming—typically under fluoroscopy—until I achieve cortical chatter and reach a diameter equal to or slightly larger than the proximal diameter of the size 1 OptiStem. Then I return to broaching. At that point, either the broach advances and seats appropriately, or the canal proves uniformly too tight and OptiStem isn’t a good option for that patient.

How do you ensure you relieve the proximal choke point without over-reaming the metaphyseal bone you’ll need for fit and stability?

Casey Whale:

I size the reamer against the planned broach and the stem’s distal geometry. If the broach is hanging up proximally, I’ll ream only up to the distal diameter of that stem size, and no more. That clears the proximal choke point without over-reaming the metaphyseal bone I need for press-fit and stability; when I return to broaching, the metaphyseal fit is preserved. If the canal remains uniformly tight from proximal to distal even after that limited ream, I take it as a sign that OptiStem may not be the right choice for that femur and I change the plan.

Exactly where do you place the two cables, what cable type/tension do you use, and when would you add a third cable?

Casey Whale:

I don’t have a strong brand preference—I’ve used Synthes and, more recently, radiolucent Arthrex cables. I always place a distal prophylactic cable before broaching. If bone quality is poor or I’m concerned about a proximal choke point creating a stress riser, I add a second cable roughly one-third of the way up the femur—i.e., around the mid-to-proximal third of the planned stem seat—where the canal begins to cone and hoop stresses tend to peak. In good bone, the single distal cable usually suffices. I tension according to the manufacturer’s recommendations rather than a fixed number. A third cable is uncommon and reserved for very poor bone or if a cortical split occurs intraoperatively.

How reliably does upsizing one stem size yield ~5 mm proud across sizes, and how do you verify you’ve restored length without shifting the joint line or over-stuffing the extensor mechanism?

Casey Whale:

It’s very reliable. Upsizing one stem size consistently brings the implant about 5 mm prouder across sizes. To verify I’ve restored length without shifting the joint line or over-stuffing the extensor mechanism, my checks depend on the construct. In a distal femoral replacement, where the MCL and LCL are sacrificed, I rely primarily on patellar height and tracking. In a hinged total knee, I corroborate patellar height with additional landmarks—the tibial resection level, tibial height, fibular head height—and I assess LCL tension. If those cues indicate I still need length after choosing a 0/±5 mm adapter, I’ll upsize the stem one size and, when necessary, combine that with a +5 mm adapter for further adjustment, rather than altering other components.

If the fibular head or patellar tendon length is abnormal, what alternative landmarks or tools do you trust to re-establish the tibial joint line?

Casey Whale:

It depends on whether we’re talking about a hinge construct or a distal femoral replacement. In distal femoral replacement, I rely primarily on patellar tracking and patellar height to re-establish the joint line. If it’s a periprosthetic fracture, I first anatomically realign the fracture and then mark a minimal distal femoral resection; if I can recreate the distal femur anatomically, that minimal resection reliably recreates the joint line. When the fracture is highly comminuted and standard landmarks are unreliable, I again default to patellar height and tracking as my main guides. The fibular head height is less helpful in a DFR scenario—the priority is restoring normal patellar tracking. Once overall alignment and limb length are restored, I set the distal femoral cut to that minimal resection measurement.

When do you prefer −5 vs. +5 adapters, and when do you combine adapter change with stem upsizing? Any pitfalls to watch out for?

Casey Whale:

I don’t favor −5 or +5 on principle—I use whatever restores a normal joint line, length, and soft-tissue tension. In very distal periprosthetic fractures, I often choose the −5 adapter because it lets me take a slightly smaller distal femoral resection while still hitting the joint line. If, after picking the adapter, I still need length, I’ll upsize the stem one size to bring it ~5 mm prouder; you can combine stem upsizing with either adapter if needed. The main pitfalls are overstuffing the joint and unintentionally shifting the joint line, which can drive patellar maltracking or collateral imbalance—so I always confirm against tibial landmarks and patellar tracking before committing.

Which intra-op tests guide your 5-degree “clicks,” and how do you reconcile conflicts between ideal tracking and the stem’s seated position?

Casey Whale:

Rotation is driven primarily by patellar tracking through a full flexion–extension arc. I use the adapter’s 5-degree clicks to dial rotation until the patella tracks centrally without tilt. I do not try to rotate the stem—the stem sits where the broach seats—and all fine-tuning happens at the adapter.

In a hinged construct, it’s a bit more nuanced because some soft tissues (often the LCL) are still functional. If excessive external rotation fixes patellar tracking but over-tensions the LCL in flexion, I back off a click or two and perform a limited lateral release to balance tracking without overloading the ligament. In a distal femoral replacement—where the native ligaments are gone—I set rotation entirely by what yields the best patellar tracking. Whatever adapter setting gives smooth, central tracking is the one I use.

How do femoral bow and diaphyseal curvature influence your choice when applying the “two cortical diameters beyond the defect” rule? Do you template with long-leg films/CT, and when is “less than two diameters” acceptable?

Casey Whale:

If I know preoperatively that I’ll need to bypass a defect—and I’ve seen the patient in clinic—I template on long-leg alignment films. In urgent or unplanned situations where I don’t have that convenience, I don’t routinely obtain a CT because it rarely changes my plan; instead, I use intraoperative fluoroscopy to confirm canal fit, account for the femoral bow, and verify that I’m clearing the defect appropriately.

With the available stem lengths (100, 130, 160 mm), achieving at least two cortical diameters beyond the defect hasn’t been a problem. In principle, you could accept less than two cortices if you achieve a very tight diaphyseal fit, but I don’t have data to define a safe lower limit, and I haven’t needed to go below two.

As for femoral bow/diaphyseal curvature, they mainly influence how long I can safely go: I choose the shortest stem that clears the defect by ≥2 cortices without fighting the bow or risking anterior cortical perforation. Going longer than that doesn’t add value and can increase risk.

Should a cortical split occur despite cabling, what’s your bailout, and do you ever convert to a different fixation concept?

Casey Whale:

This is actually the only OptiStem failure I’ve had so far—and it was on me. The patient had a long lateral femoral plate and very poor bone. I removed the distal screws but intentionally left a mid-plate screw that, on my template and intraoperative X-ray, looked just proximal enough for the stem to clear. In reality, that screw deflected the stem anteriorly, created a cortical fracture I didn’t appreciate intraoperatively, and at first follow-up the fracture had propagated with stem subsidence.

I didn’t change fixation concepts or revise the stem. Instead, I added an anterior plate and multiple cables over the existing lateral plate. She went on to heal uneventfully and, at about six months, had solid union with a stable construct. The takeaway for me: if there’s any chance a retained screw will impinge on the stem, remove it. If a cortical split does occur despite cabling, supplemental plating plus additional cables can be an effective bailout without converting to a different fixation strategy.

What X-ray signs reassure you of osseointegration vs. early subsidence with OptiStem, and what does your follow-up schedule look like in the first 12–24 months?

Casey Whale:

Radiographically, I compare the immediate post-op film with follow-ups and look for a stable stem position—no progressive radiolucent lines and no change in axial seating or varus/valgus alignment. All press-fit stems can show a millimeter or two of trivial early settling if you scrutinize the images, but in my OptiStem series I haven’t seen any clinically meaningful subsidence. My routine follow-up is at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 1 year; beyond 12 months I follow up as clinically indicated.

Is there anything you would like to add or any points and remarks you would like to make?

Casey Whale:

The main reason I’ve gravitated to OptiStem over other fixation—both press-fit and cemented—is how reliably it locks in once you have the right canal fit. Even the smooth trial often requires an impactor to remove after broaching, which tells you how well the taper engages. In my series, that geometry has translated into excellent stability with no clinically meaningful subsidence or early loosening. The keys are careful patient selection, prophylactic cabling to manage hoop stress, and avoiding excessive proximal reaming. If you respect those principles, the construct has been very dependable.